How Mdm Foo Kui Lian built Tian Tian Hainanese Chicken Rice into a Singapore icon

Mdm Foo Kui Lian, who spent her childhood in a kampong (village), is the matriarch behind Tian Tian Hainanese Chicken Rice, one of Singapore's most iconic hawker stalls, and a name cherished by generations.

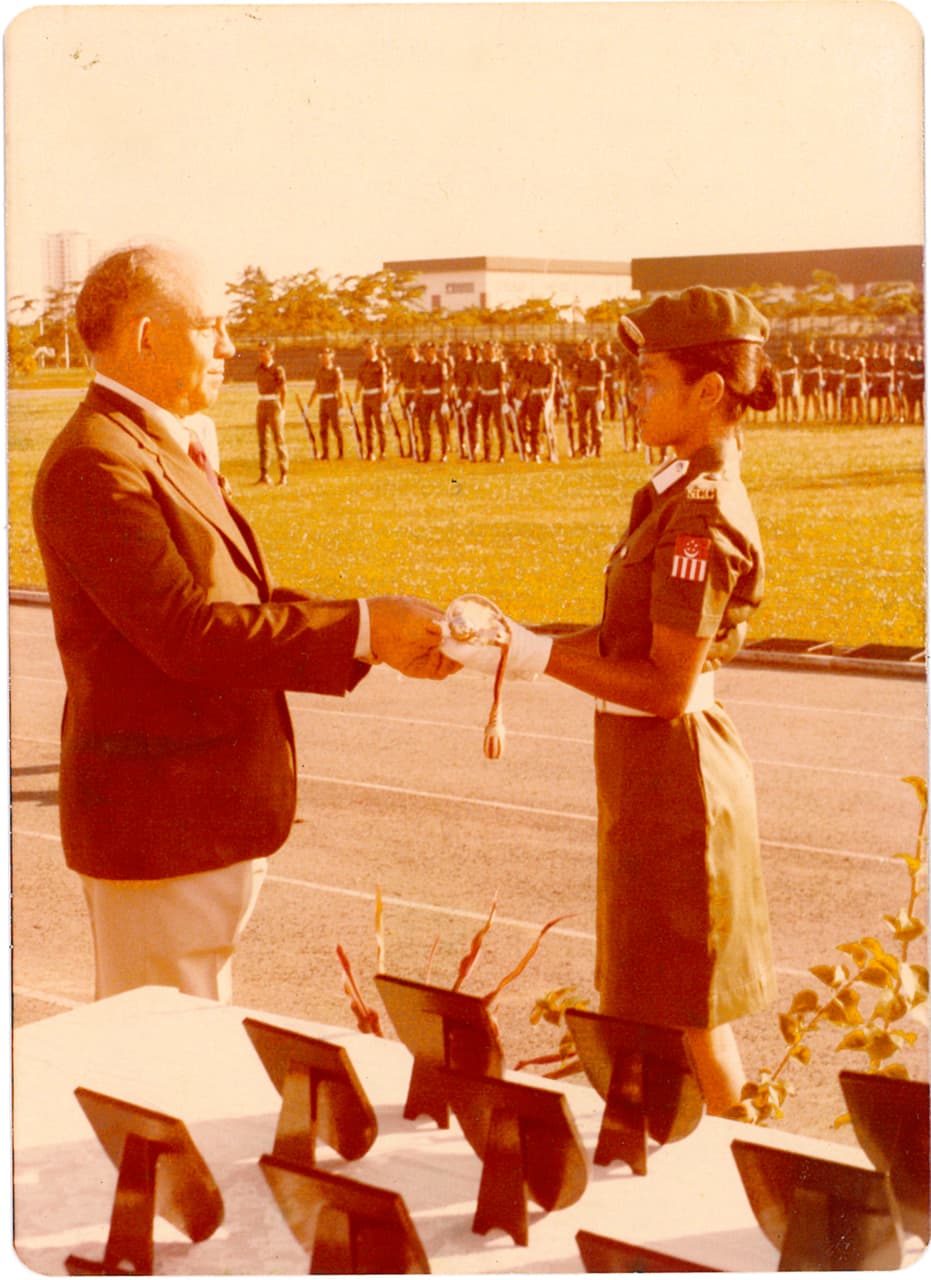

As a young girl growing up near Thomson Road in the 1960s, Mdm Foo Kui Lian learned early what it meant to work hard.

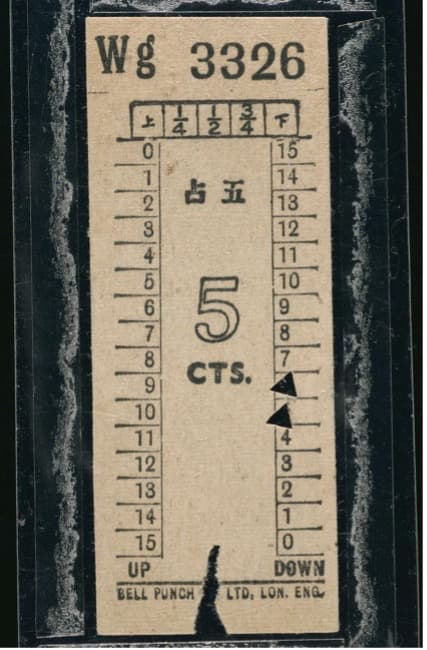

Each morning, she would rise before dawn to catch the bus to the market, returning with heavy bags of fresh produce. It was a simple routine, but one that taught her discipline and determination - values that would later define her path as a hawker.

Over nearly 40 years, Mdm Foo – alongside her husband and daughter – built Tian Tian Hainanese Chicken Rice from a single stall into one of Singapore's most celebrated hawker brands. Today, the brand is recognised across the island and beyond, with fans ranging from loyal regulars to global culinary icons like the Gordon Ramsay and the late Anthony Bourdain.

Here's her story.

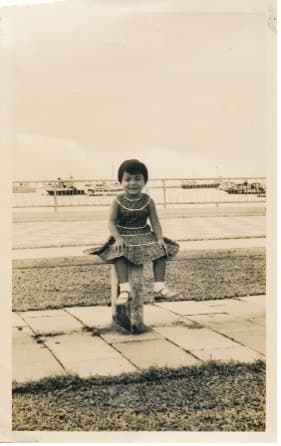

A childhood rooted in resilience

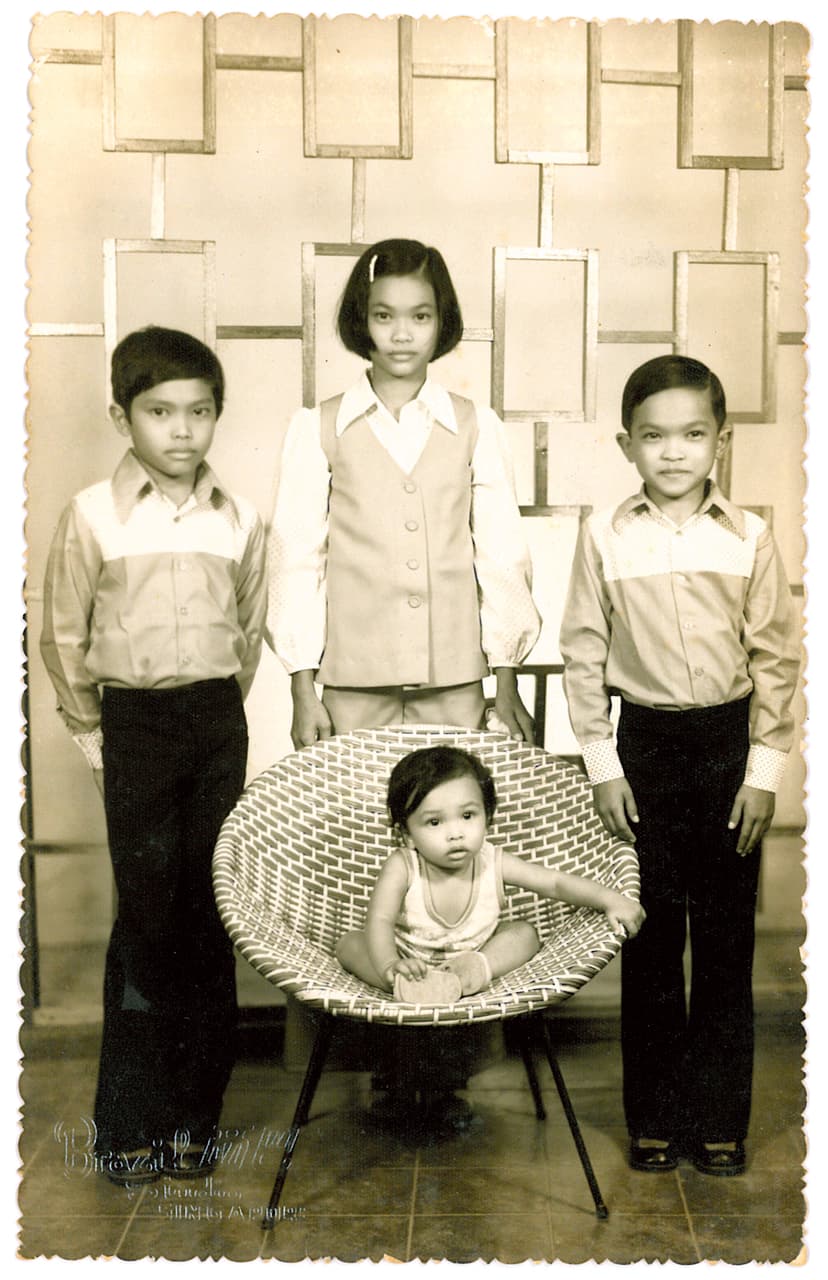

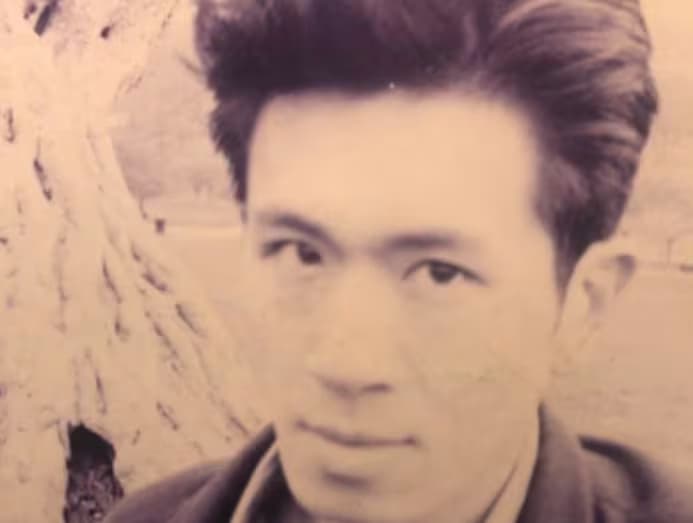

Mdm Foo Kui Lian is a first-generation Singaporean of Chinese Hainanese descent.

She grew up in a large family of eight, living in a rented room along Thomson Road. Her parents had come to Singapore from Hainan Island in search of a better life and, like many others of their generation, they made do with what they had.

"We didn't eat meat often, maybe just during Chinese New Year," she recalls. "Most days, we had vegetables like sweet potato leaves. They were simple but delicious."

She and her siblings would walk to school through open fields, past small shops and quiet roads. While much of that landscape has since changed, her memories of the place remain as vivid as ever. "It looks completely different now," she says. "I went back once to find my old neighbourhood, but there wasn't much I recognised."

Even though Mdm Foo's mind often wanders back to simpler times, her focus remains on the journey that has brought her where she is. "I'm proud of how far Singapore has come," she says, "and I am even prouder to have played a hand in the shaping of its food culture."

Stepping into the world of chicken rice

Mdm Foo's love for chicken rice began long before she even learned how to make it herself.

As a child, she looked forward to the visits of a neighbour who would bring over chicken rice balls for her family. "We were always so happy when she came around," she recalls. "Those rice balls were delicious. You just don't see them anymore."

Later, in the 1960s, her brother introduced her to the original Swee Kee Chicken Rice stall. "At that time, they raised their own chickens, and you could even choose the one you wanted. That really left an impression on me," she recalls.

Those early experiences planted the seeds of a lifelong passion. In 1986, she and her brother decided to open their own chicken rice stall at Maxwell Food Centre, a name now synonymous with Singapore's hawker scene.

They called it Tian Tian, meaning "every day" in Mandarin, as a promise to serve food that customers could enjoy daily.

Mdm Foo fully dedicated herself to running the stall. "Back then, I was fully focused on the stall," she says. "I used to wake up before dawn, catch the bus to the market, and carry back bags of fresh bean sprouts, cucumbers, chillies, basically everything we needed for the day."

To find the best ingredients, she often travelled all the way from Thomson to the Pasir Panjang wholesale market. It was a time-consuming and physically demanding routine, especially on rainy days. "It was tiring, but necessary," she recalls.

Things have changed since then. "Now, suppliers deliver directly to the stall, which makes things much easier," she says. "But I still keep a close eye on everything. My care and attention haven't changed since the day we first started."

Taking over Tian Tian Hainanese Chicken Rice

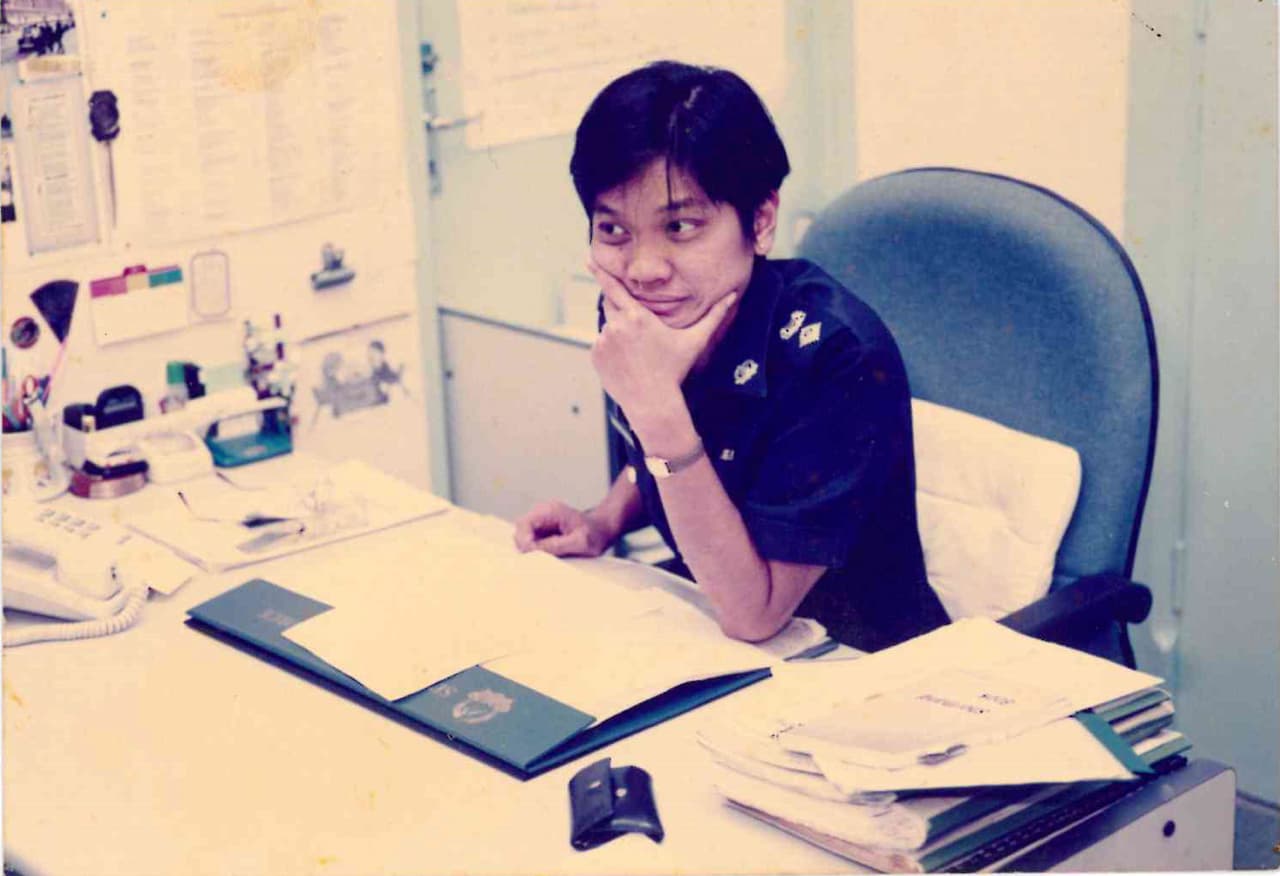

When her elder brother retired two years into the business, Mdm Foo stepped up to run the stall with her husband, who was working as a lorry driver at the time.

"In the beginning, it was just the two of us," she shares. "He would drive me to the market before dawn, and we would hand-pick every ingredient. We even made our own garlic paste and chilli sauce from scratch using the best Malaysian and Thai chillies. Nothing was outsourced."

The work was demanding, but Mdm Foo remained committed to doing things the right way. As the business grew, she brought in staff to help with tasks like chopping and service, but she stayed hands-on in the kitchen.

"There are just some things I needed to do myself, such as preparing the sauces and getting everything ready for the day," she says.

Tian Tian Hainanese Chicken Rice quickly built a reputation for doing the simple things exceptionally well. The rice was fluffy and fragrant, never too oily or overly soft. The poached chicken was consistently tender and full of flavour, perfectly complemented by their signature in-house garlic-chilli sauce.

Customers kept coming back not just for the taste, but for the consistency. Word spread organically: taxi drivers recommended the stall to their passengers, and loyal regulars brought along friends and family.

Mdm Foo was unaware that her humble chicken rice had gained international acclaim until tourists began showing up with guidebooks in hand, printed in various languages, pointing to her stall with wide, eager smiles.

Even today, queues remain a familiar sight at Maxwell Food Centre — a quiet testament to the care, precision, and pride poured into every plate.

Leaving a legacy in Singapore’s hawker scene

Thanks to Mdm Foo's unwavering dedication and hands-on care, Tian Tian Hainanese Chicken Rice has become one of Singapore's most recognisable hawker brands.

The flagship stall at Maxwell Food Centre remains a favourite among locals, while new outlets in Simpang Bedok, Clementi, Lucky Plaza and Bishan have brought their signature dishes to even more diners.

Over the years, Tian Tian has garnered numerous accolades. It has been featured in the Michelin Guide, spotlighted by the Singapore Tourism Board, honoured with the Singapore Prestige Brand Award, and regularly voted as a must-visit place for Hainanese chicken rice.

Some of the world's top chefs have also taken notice. The late American celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain was among the first to bring international attention to Tian Tian.

"When he arrived, we had no idea who he was," Mdm Foo recalls. "He came early, quietly took photos and observed us working. He stayed past midnight doing his research."

Bourdain went on to feature Tian Tian in his show and even proposed bringing Mdm Foo to New York to open a stall. While rental permit issues in the US meant the trip never happened, the experience remains a proud moment for her.

In contrast, British celebrity chef Gordon Ramsay's visit was anything but low-key.

"The crowd that day was incredible," she recalls with a laugh. "People were even climbing onto tables just to catch a glimpse of him. It got so hectic that filming had to be cut short."

Despite his fiery TV persona on shows like Hell's Kitchen and Kitchen Nightmares, Ramsay was surprisingly warm and respectful.

"Everyone told me to be ready to scold him if he gave me a hard time," she smiles. "But he was very friendly. He came in and immediately recognised every ingredient we used. He truly understood how our food was made."

The road ahead for Tian Tian Hainanese Chicken Rice

Despite the recognition Mdm Foo has received over the years, she remains committed to the values that built the business from the ground up.

"Running a family business requires more than just hard work," she says. "You have to be involved in every detail and stay dedicated. Quality and consistency are everything."

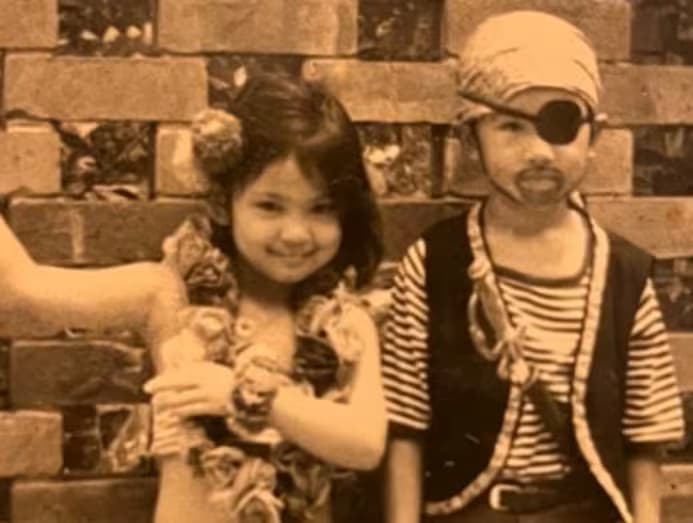

"My daughter, Mui Yin, and I are very particular about keeping the taste just right. When customers give feedback, we listen carefully and make improvements," she continues.

Looking ahead, Mdm Foo is focused on preserving what makes Tian Tian special. Mui Yin now plays a vital role in managing the stall. Having grown up helping out, she understands the demands and care the business requires.

"It isn't easy work, and it's rare to find young people today willing to put in that kind of effort," Mdm Foo notes. "But she knows what it takes and is ready to do it."

For now, the family has no plans to turn Tian Tian into a commercial enterprise. Mdm Foo's priority remains clear: to keep the heart of the business alive by being dedicated to serving homely, hearty food.

Mdm Foo’s hopes for the future of Singapore

As Singapore nears its sixtieth year of independence, Mdm Foo reflects on the nation's transformation and what she hopes lies ahead.

"Everything has changed; the buildings, the streets, even how we live," she says. "But I hope the kampong spirit, that sense of community and looking out for one another, stays with us."

Now in her later years, Mdm Foo wishes for a safe and caring Singapore, especially for younger generations. She hopes they continue to value their cultural roots, including the hawker food that has long been a unifying thread in Singaporean life.

"Hawker food is more than a meal," she says. "It connects people and holds memories. It has fed generations and helped shape our identity as a nation."

And while challenges such as rising costs and changing tastes remain, Mdm Foo remains optimistic. "I'm encouraged by how many are starting home-based food businesses and finding new ways to share our local flavours. That gives me hope."

Having spent a lifetime in the trade, she knows that preserving Singapore's food culture goes beyond recipes. It's about the care, effort and heart poured into every dish.

"I'm proud of how far we've come," she says. "And I hope we keep moving forward without losing sight of what truly matters."

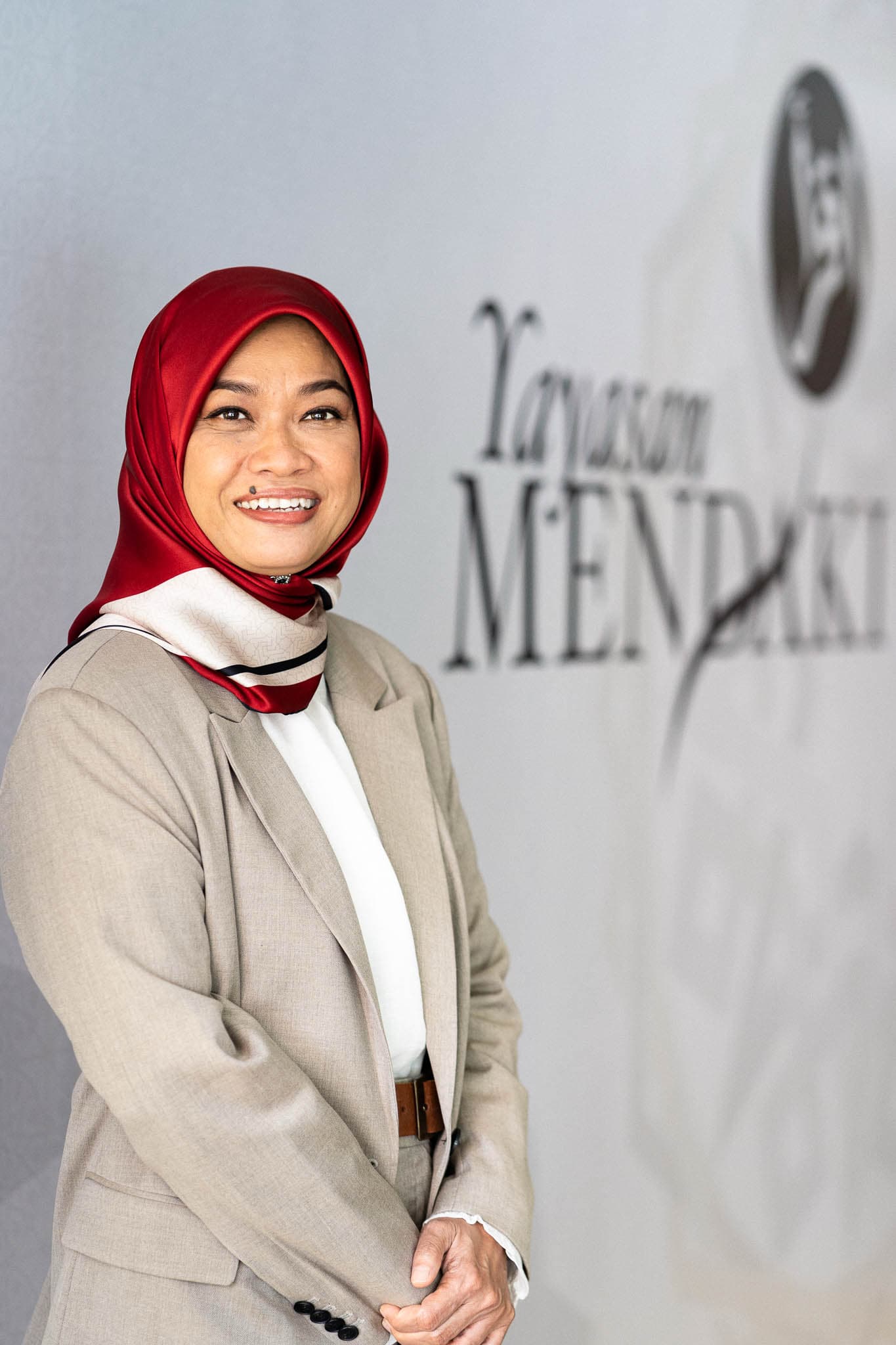

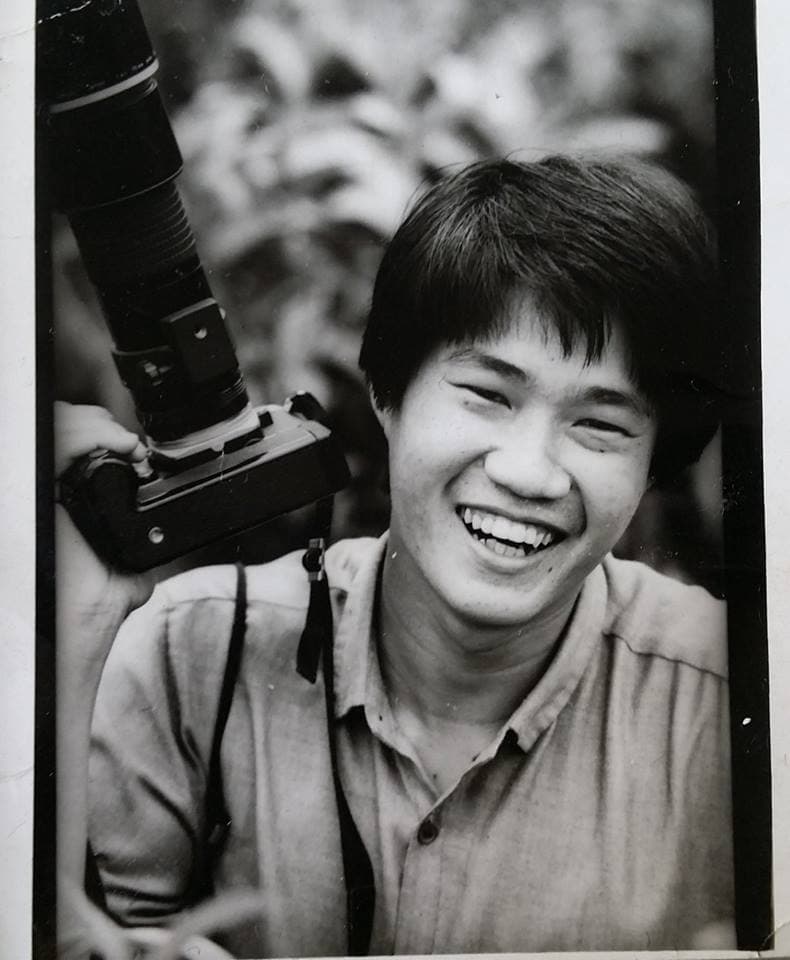

Meet Mdm Foo.

Founder. Hawker icon. Champion of authentic Hainanese flavours. Since opening Tian Tian Hainanese Chicken Rice in 1986, Mdm Foo Kui Lian has built a legacy rooted in quality, dedication, and heart.

Today, Tian Tian is a household name in Singapore and a must-try for food lovers around the world.

Visit Tian Tian Chicken Rice's website here.